A communications and educational challenge

One in three Canadians thinks so!

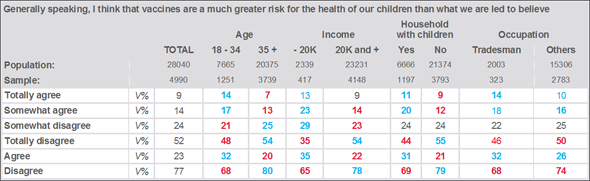

In these days of concern about a possible coronavirus pandemic, I remembered a question that we asked last year in our study of the values of Canadians about the attitude to vaccines. Even though we have not found a vaccine for this current virus, the issue continues to be topical, especially when 23% of Canadians agree with the notion that "vaccines pose a greater risk to the health of our children than we are led to believe"!

Diseases that were thought to be eradicated are re-emerging and are at risk of spreading rapidly if such a sizable proportion of the population persists in its scepticism toward vaccinations or simply decides not to get vaccinated or not to get their children vaccinated. We need only recall the medical alert declared in Portland, Oregon, last year, when nearly 200 cases of measles were identified, including in individuals who had never been vaccinated. This region in the United States is one of the most resistant to vaccinations. Smaller outbreaks have also occurred in Canada, including in Quebec, as well as in Europe and elsewhere in the world in recent years.

On February 6th, NBC reported the death of a four-year-old child in Colorado from influenza after his mother refused to give him antivirals because of "advice" on the Facebook page of an anti-vaxxeers group!

Thus, misinformation on the subject abounds on the Internet and on social media, warning that vaccinations have more potential risks than benefits. Some content even makes a causal link between autism and vaccinations! All this has been debunked by the health and scientific authorities. Yet, despite everything, even people with the best interests of their children at heart believe these pseudo-scientific theories, while running the risk of a resurgence in and the spread of infectious diseases that have been beaten in the past, such as measles, rubella and mumps!

Une personne sur quatre au pays pense que oui! - copy

The socio-economic and demographic characteristics of this phenomenon is very apparent. Even if we cannot project the profile to every one of these "sceptics," in general, this distrust of vaccinations is clearly over-represented in people with children, in those under 35, in those with the lowest incomes and levels of education in society, as well as among blue-collar workers.

Note that there are no real regional differences across the country on this question, except perhaps a slight over-representation in Quebec at 26%.

Thus, economic and social vulnerability constitutes a breeding ground for this scepticism toward vaccines, potentially fertile ground for the disinformation about the alleged dangers of vaccinations. Parental worry and lack of critical benchmarks (low levels of education) among these groups encourage a receptiveness to these anti-vaccine discourses. Not only do they have to deal with the rigours of a difficult lot in life, they also have to worry that their children might be in danger!

Fatalism and cynicism toward the elites

Beyond their difficult socio-economic situation, our analyses indicate that the "mental postures," view of life and personal values of these sceptics are even more decisive in explaining their distrust of vaccinations: a "sociocultural" profile influenced notably by their low levels of education and income.

Indeed, on a statistical level, we clearly see that they express an extremely fatalistic view of life, associated with a deep sense of lack of control. They feel burdened by a life full of uncertainties: that there is absolutely nothing they can do to change the course of their lives or even improve their lot. For them, life is nothing more than a series of challenges, with the worst yet to come!

This feeling pervades almost every aspect of their lives. They expect things to go wrong. If they are going to catch a disease, there is nothing they can do about it, vaccinated or not. And now, what if vaccines are the cause of even more problems?

Our findings tell us that they have little confidence in society's elites. Their view of life is very "Darwinist." For them, life is all about winners and losers, and they certainly see themselves among the latter group. For them, the elites, no matter which ones - political, business, scientific, journalists, etc. - have only one goal: to enrich themselves and gain power at the expense of the common good. They are convinced that there is an ongoing conflict of interest, a conspiracy, that is marginalizing them.

They tend to believe that vaccines serve only to enrich the pharmaceutical companies and, by extension, doctors and politicians, without any consideration for the population.

Hence, their fatalism, cynical attitude toward the elites and Darwinist view of society produce a very receptive audience for the dissemination of fake information about vaccinations.

A communications and educational challenge

This type of socio-cultural context poses a major challenge for public health authorities. Short of politicians making vaccinations compulsory, awareness campaigns will encounter resistance (from potentially up to one in four people in the country). These sceptics do not consider health and scientific authorities to be credible, but rather complicit in a plot hatched by the elites. There's no point in invoking rational scientific fact, they simply refuse to believe it, while denouncing what they perceive as a conflict of interest.

On the other hand, when we analyze their hot buttons more closely, we find some potential levers that could lead them to modify their positions.

They place great importance on their networks of "friends" and acquaintances, while expressing a strong need for recognition. They may very well allow themselves to be convinced of a different point of view if it comes from people they admire and / or from influencers they follow.

An effective communications strategy aimed at reducing the influence of this movement of distrust should therefore be based on word of mouth and the relaying of information by credible influencers within these communities of vaccine opponents.

These sceptical groups must be infiltrated in order to propagate the truth. The idea is to encourage conversations on the issue among credible and trusted individuals (friends, influencers, etc.). This way of disseminating information is often used in marketing communications when dealing with segments of individuals who no longer trust traditional advertising.

Furthermore, these distrustful individuals also display a very strong sense of social responsibility and a willingness to help one other. Vaccinations could therefore become a vector of social responsibility in these targeted conversations.

Thus, the cause is not completely lost, even though the proportion of sceptics in Canada may appear alarming.

One simply has to find the right communications approach.