Feeling socially excluded is not a mental illness but its effects can be just as toxic and destructive!

In recent weeks, Quebec has witnessed an unprecedented series of unspeakably violent tragedies. Although most Western countries, including the other Canadian provinces, have witnessed this kind of tragedy all too often, Quebec is not used to such frequent attacks, especially of the kind that uses a vehicle as a weapon to run over children in a daycare (Laval) or pedestrians in a peaceful village in the Bas-Saint-Laurent (Amqui).

These tragedies are reminiscent of a similar mass murder in Toronto in April 2018, when a man used the same vehicle-ramming tactic on a Yonge Street sidewalk, killing 10 people and injuring 15.

These latest tragic events in Quebec have launched a debate about mental illness. The premise, while not entirely without merit, postulates that to commit such heinous crimes, the perpetrators cannot be in their right mind.

Although this kind of reasoning may seem legitimate, many studies on the subject have established that only a minority of these seemingly insane acts are the work of individuals suffering from a mental illness diagnosable by a psychiatrist or mental-health specialist.

According to these studies, the vast majority of these acts are the result of social marginalization, the feeling of being disconnected or disengaged from the people around you or from society at large.

Obviously, our surveys cannot detect which individuals suffering from marginalization might commit such crimes. But if we accept the theory that social disconnect could be a trigger for these killings, we have an easy way to measure it.

Our surveys use several indicators to measure social disconnect. The two indicators we discuss below are particularly telling.

Social disconnect in the country

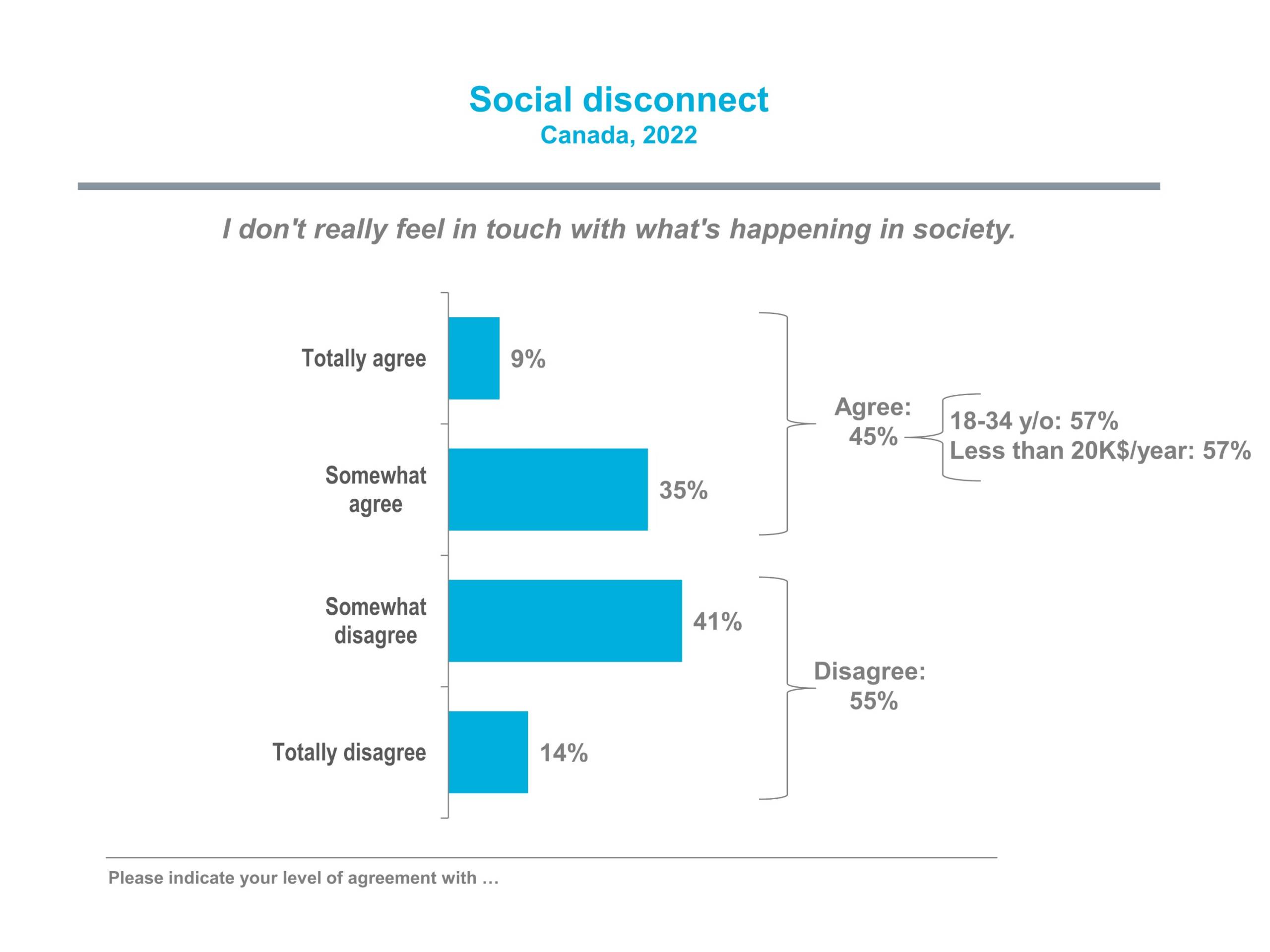

The first indicator is simply not feeling “connected” to what is happening around you.

The percentages are dramatic. More than two out of five Canadians (45%) say that they feel marginalized in society (or at least quite marginalized since a plurality – 35% – say they “somewhat” agree with our statement).

They have a “somewhat” poor ability to deal with the world around them.

What's more, this percentage (45%) rises to 57% among people 18 to 34 years of age. Income also plays a role. The same percentage (57%) applies to those with an annual income below $20,000. This means that almost three out of five people in these two segments suffer from social disconnect!

Even more striking is that 9% of Canadians say they are in complete agreement with the statement, a percentage reaching 15% among 18- to 34-year-olds.

In fact, 9% of Canadians 18 years of age and older represent some 2.7 million individuals in Canada in 2022. That's a lot of people in our society who feel disengaged and excluded! (Our studies focus almost exclusively on the adult population age 18 and over).

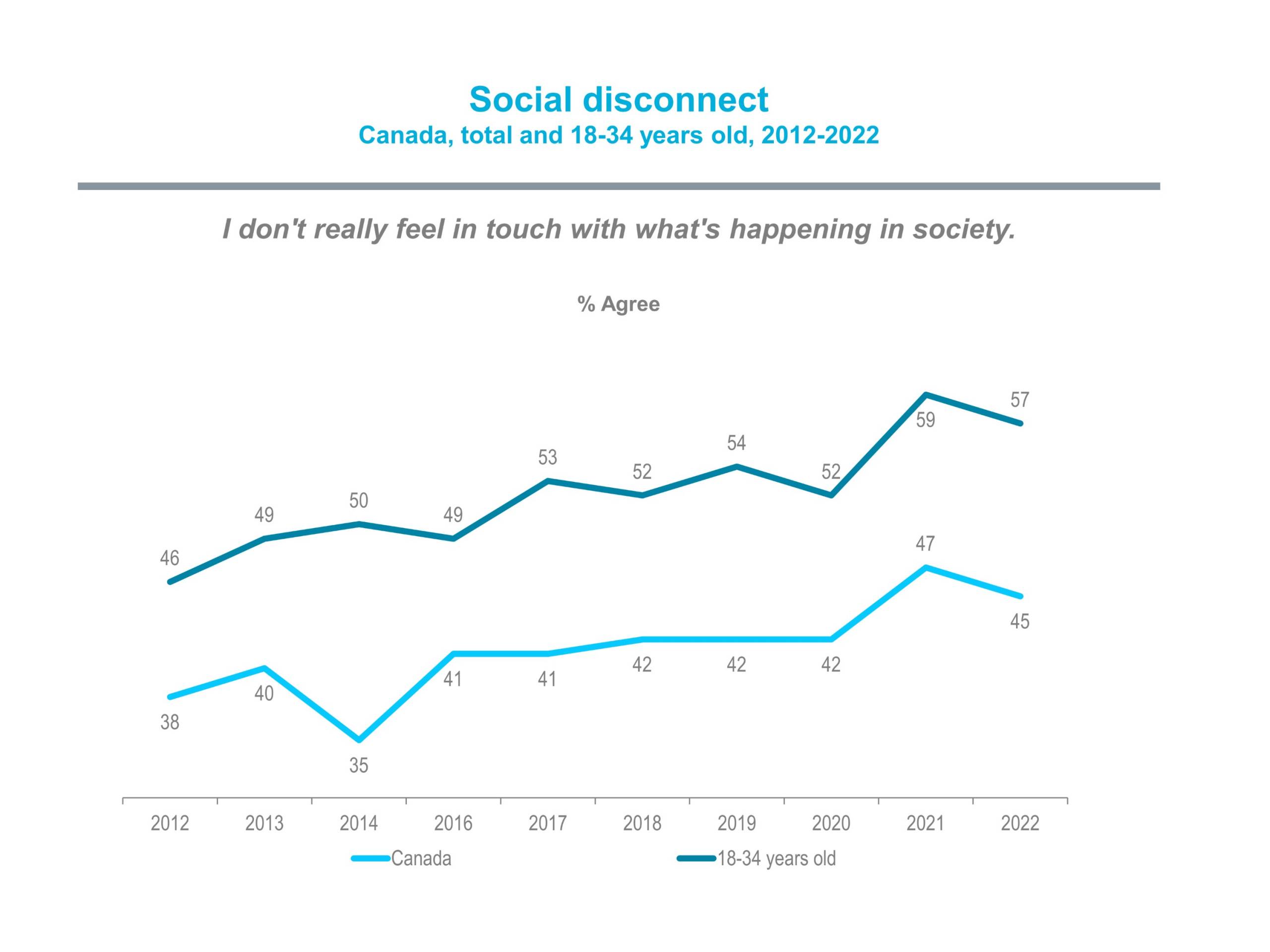

An upward trend

If the trend continues, we don’t expect this phenomenon of marginalization to abate.

Our society has been creating marginalized individuals at an accelerating rate year over year, especially among younger individuals. It seems as if the majority of these new generations entering our society are increasingly unable to find their place there!

A lack of purpose in life

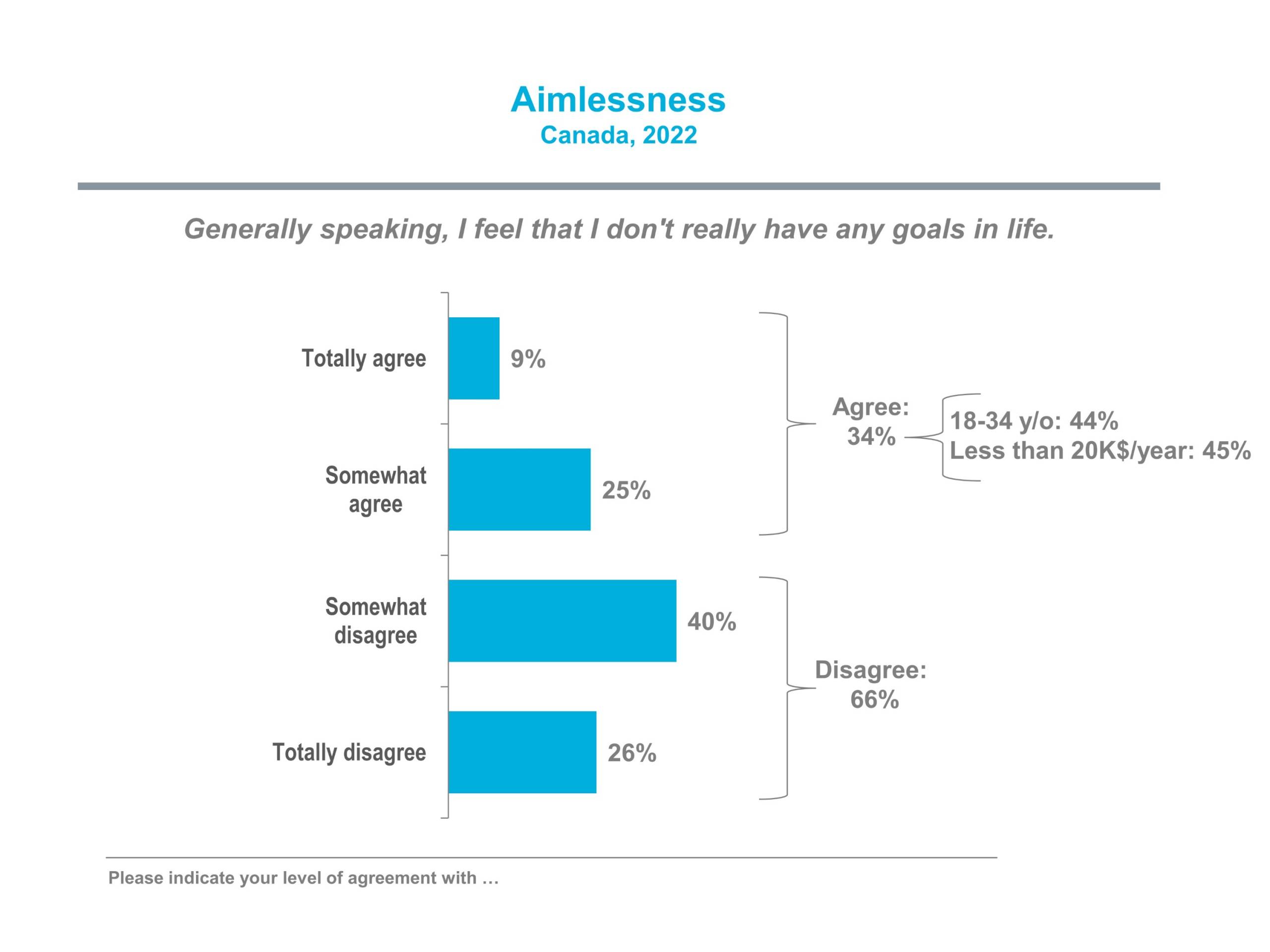

A corollary phenomenon closely associated with this feeling of societal disconnect is aimlessness – the feeling that your life has no purpose, that you are leading an existence devoid of meaning.

This feeling is expressed in proportions quite similar to that of social disconnect, as illustrated by the following table (with the same over-representation among young people).

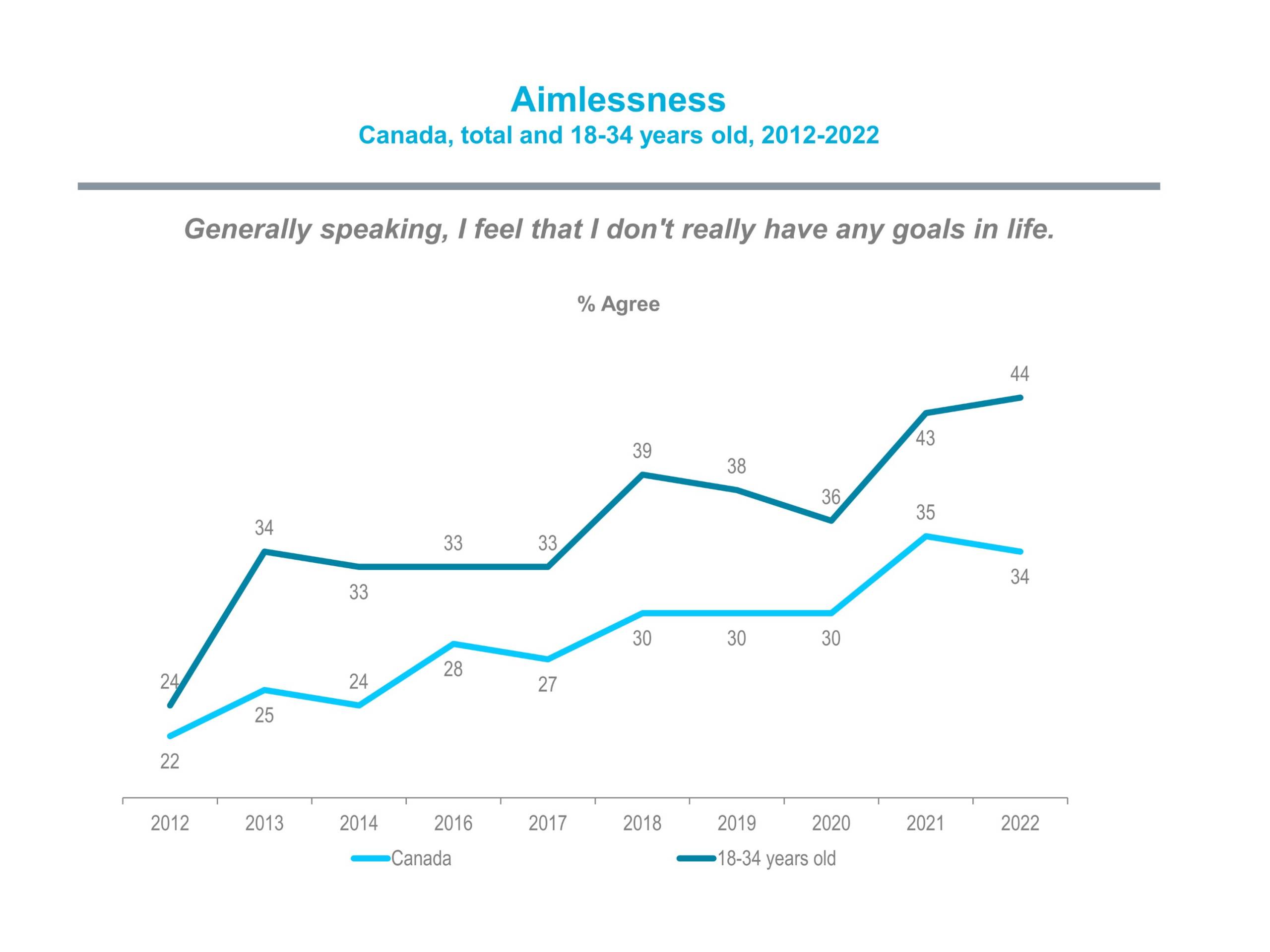

This sad trend has also been on the rise over the past 10 years, especially among the younger cohorts.

The big picture

Those two statements give us a very good indication of how difficult life is for a large and unfortunately growing proportion of the Canadian population. But these are only two of the many indicators we use to measure the sense of social exclusion and marginalization in this country.

To produce an overview of all our indicators on this issue, and above all to avoid unduly burdening the text, we have created an index that combines all the dimensions of the phenomenon. This index also allows us to monitor its evolution over the years.

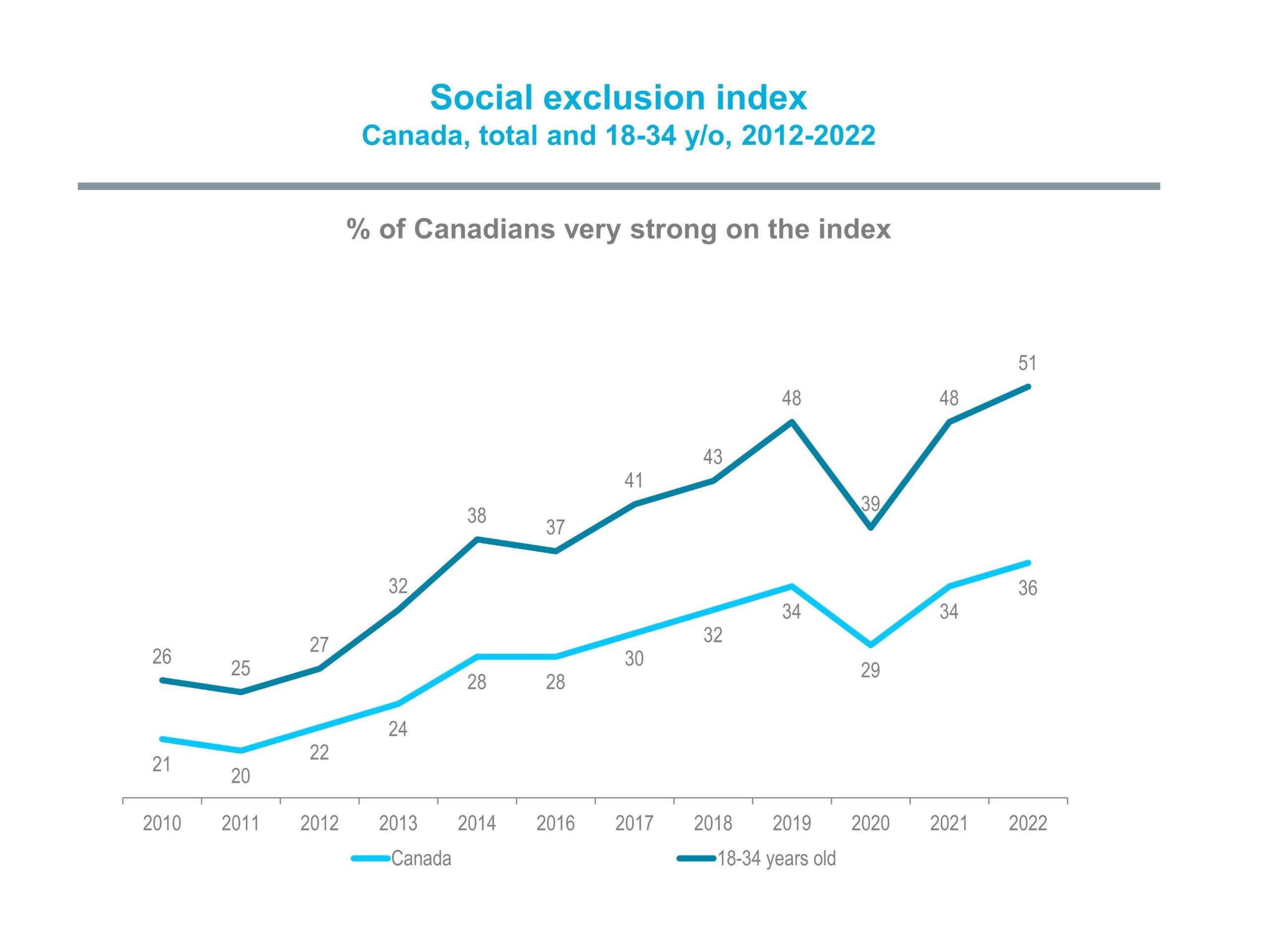

This index tells us that more than one in three Canadians in 2022 (36%) felt (very or extremely) disconnected from the people around them or marginalized in society generally – a rise of 15 points since 2012 (when this index stood at 21%). This index also measured the exceptional rise of the phenomenon among the younger generations (51% among those under 35 in 2022).

Beyond feeling disconnected from others and society and lacking purpose in life (aimless), the other measured dimensions that characterize the profile of these marginalized individuals include:

• A strong sense that they lack agency over their lives o the impression that forces beyond their control are directing their destiny (governments, markets, etc.)

• A highly fatalistic view of life (the worst is bound to happen)

• Very financially stressed

• Hoping for help from institutions but lacking faith in them or unable to access their help • Cynicism • Highly prone to civil disobedience

• Very conservative (especially on gender equity)

At a socio-demographic and socio-economic level, these are young families active in the workforce with a low socioeconomic status (income and education).

In other words, they are financially stretched and overwhelmed by the world they live in because they have trouble getting their bearings, except for meaning and hope.

Social exclusion, mayhem and violence

Our society, with its complexity, rapid pace of change and growing uncertainty, is creating exclusion. More and more individuals are no longer able to thrive in our society. Instead, they are increasingly experiencing distress and suffering or even frustration and rage.

This profile of individuals is at the root of much of the mayhem that has occurred in our society in recent years, the rise in marginalization having led to more and more opportunistic outlets (with the help of social media).

Think of the far-right movements, the examples of toxic masculinity, the Incels, the violence against women, the incidences of femicide, etc. (not to mention the truck convoy that paralyzed downtown Ottawa): all these phenomena seem to stem from feeling at odds with today's world and reacting to this discomfort with a show of force.

To recap, those who feel the most marginalized represent about 9% of the Canadian population (which is also the case for our combined index). As we said earlier, we are talking about 2.7 million people in this country!

Of this number, isn’t it conceivable that at least one person will freak out and do something heinous?

We think it is inevitable. Given our portrait of these individuals, the distress and rage they are experiencing, their perceived lack of agency over their lives and their feeling of being totally overwhelmed, it is almost surprising that explosions of staggering violence do not occur more often!

Consequently, we support the view that these unspeakable tragedies generally have little to do with mental illness, but rather with the social conditions confronting a large and growing proportion of the population.

Unfortunately, our data also lead us to conclude that, if this trend continues, eruptions of violence by society’s most marginalized, distressed, enraged and disengaged individuals, are likely to become more and more frequent.

Let’s hope we are wrong!